UNDERSTANDING ∀ GUNDAM IN TODAY’S CONTEXT

UNDERSTANDING ∀ GUNDAM IN TODAY’S CONTEXT

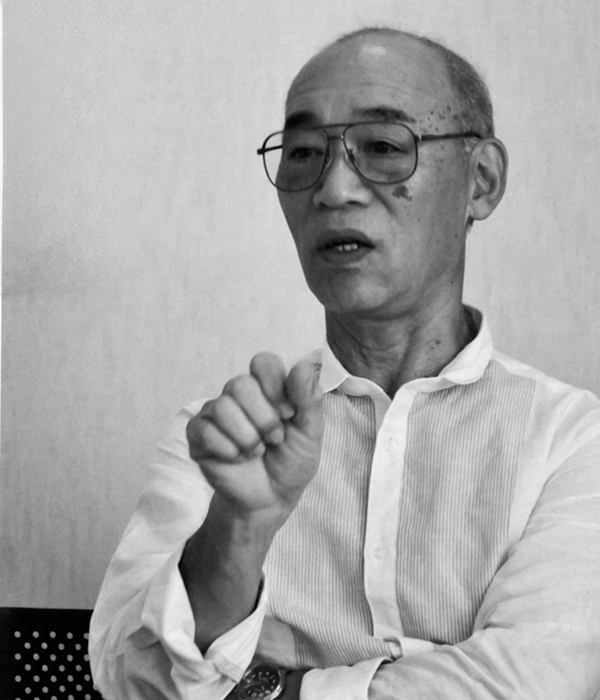

Crafted as Gundam’s 20th-anniversary piece, ∀ (Turn A) Gundam has now been with us for over a decade. Reflecting on its place in the anime pantheon, it’s undeniable that this work stands out – not just as a mecha series or a Gundam installment, but as a unique animation in its own right. And even after ten years, that assessment likely remains unchanged. But why? One of the key elements in Turn A Gundam’s narrative is the concept of “the moment when an era begins to shift.” Fast forward to 2011, and we witnessed the Great East Japan Earthquake followed by the nuclear disaster – events that may well be viewed as historical turning points. While the circumstances differ greatly, revisiting Turn A Gundam through this lens reveals a wealth of insights. That’s why we’ve sat down with Director Tomino to discuss the series from both its original perspective and through today’s eyes.

THE UNEXPECTED CONNECTION BETWEEN THE 3.11 DISASTER AND TURN A GUNDAM

――In the wake of the disaster, many creators, including manga artists, grappled with the question: “Is it appropriate to create art at a time like this?” This prompted me to consider the role of fiction in such turbulent times. And that’s when Turn A Gundam sprang to mind. While Turn A Gundam portrays the birth pangs of a new era, and the post-disaster reality saw the collapse of our established norms – two seemingly opposite scenarios – I felt that Gundam as a work resonated with our current post-disaster world. That’s why I wanted to have this conversation today.

Tomino: That’s a delicate topic to discuss carelessly. Turn A Gundam was conceived with precisely these kinds of scenarios in mind, and reality has, in a sense, caught up with it. Take the nuclear power issue, for instance. Previously, we needed to explain and help people understand the problems with nuclear energy. But post-Fukushima, these issues have become starkly visible, both in images and reality. While this might make it easier for me to speak about certain topics outside of creating anime, it’s also incredibly dangerous. But without such foresight, I wouldn’t create works like Turn A Gundam.

When creating Gundam, what was I envisioning? The reality is that humans can’t forget war. First, there are policies that lead to war, which, simply put, are driven by economics. Economic stimulation can be effectively achieved through war because it necessitates consumption. The intensification of economic supremacy inevitably leads to war. This is one of the things I wanted to express through “Gundam.” Economic supremacy idealizes modern economic leaders, forming the foundation of politics and diplomacy. Therefore, with them as leaders, war inevitably escalates. The Universal Century depicts our inability to break free from such wars. I decided to create Turn A Gundam to explore what becomes of humanity when we consider all of this history. People who only understand war driven by economics are bound to collapse. It’s beyond human wisdom and can only end in termination. What’s crucial in human life is creating a world where Queen Dianna can sleep peacefully. That’s the essence. The ending of Turn A Gundam was considered challenging for a mecha anime. But in reality, it’s not. In the past, I had to explain this, but post-Fukushima, it’s become easier to understand. Perhaps that’s why Turn A Gundam is appreciated now more than ever.

THE SURPRISING REASON BEHIND TURN A’S UNORTHODOX ENDING

――Indeed, Turn A Gundam’s ending was quite extraordinary. It didn’t just show what happened to the characters; it delved into their lives and philosophies. Gundam series have always been unique in that even supporting characters aren’t mere pawns for plot devices. They bring their own values and perspectives to the screen. While this can make the story more complex, it’s also a major part of its appeal.

Tomino: Turn A Gundam may have been influenced by elite think tanks, but it also succeeded in capturing everyday sensibilities. I believe real history is built on accumulated human relationships. That’s why I agonized over the ending for six months. There’s no point in depicting victory through tactics, ideology, or power dynamics. When we were making Turn A Gundam, Star Wars: The Phantom Menace was a hit, but I didn’t want to portray victory like that. I wanted to ground the meaning of victory in the everyday. As an older director, I wanted to do something young directors wouldn’t – make a robot show that even traditionalists could appreciate. The staff understood this, which is why we were able to create that kind of ending. In hindsight, it’s natural that it’s become a work worth revisiting post-Fukushima. That’s precisely why I’ve started to be cautious about speaking on disasters like Fukushima outside of anime. But I thought if we could discuss it in relation to Turn A, it might be worth talking about.

――On one hand, Turn A Gundam offers an answer to what war means for humanity. Why do you think this seems to overlap with the Fukushima issue?

Tomino: The nuclear accident is even more dangerous than war. The mindset of those who claimed there was no radiation damage is no different from the blind faith of those who insisted Japan could never lose the war. Post-Fukushima, it’s become clear that politicians and businessmen who only think about immediate profits are truly the nation’s downfall. The thinking of intellectuals is dangerous, you know. A crucial backdrop to the Meiji Restoration was that even at the domain level, there was always a readiness for war. This became the face of the Meiji government and drove the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars. In other words, there was a reality to war and national defense. But from the late Meiji era onwards, we lost the ability to envision a grand design, and elites focused on ministerial interests proliferated. Even the army and navy became preoccupied with turf wars, losing sight of protecting Japan. While they thought they were defending the nation, they were actually leading it to ruin. The nuclear power situation is exactly the same – TEPCO became just another salaryman company, not a corporation supporting the foundation of society through electricity, so they didn’t consider national interests or the land. The difference between war and nuclear disasters is that war is temporary, but radiation issues never end. It could potentially make the land uninhabitable for centuries. I wanted to express through anime that we can’t afford to have such low-level intellectuals in power who can’t understand this, but if you do it too seriously, the work becomes uninteresting.

I question whether economic-driven globalization is really the right path. In contrast, those working on the ground know the importance of maintaining human relationships. Recently, I’ve come to think that this might be the true source of people’s strength, and by extension, national strength. I often feel that people on the ground, at the grassroots level, have more insight. They know that history is made through human interactions, but have thinkers and politicians really been making history? How much of what we learned in peaceful Japan has actually been useful? Why couldn’t we hear these voices in our education? Thinking about this, I began to doubt the values created by intellectuals.

THE CRUCIAL DISTINCTION BETWEEN TURN A GUNDAM AND GUNDAM

――One question that’s been nagging at me is why we haven’t seen any follow-up works in the vein of Turn A. Even if it didn’t appeal to all generations, it seemed to resonate with older viewers. Wouldn’t that present a business opportunity?

Tomino: Turn A Gundam wasn’t imitated because it’s a definitive work that’s difficult to copy. However, in terms of entertainment, it’s easier to shape public opinion by creating works that can be imitated. Gundam has been copied extensively. Even “run-of-the-mill intellectuals” who grew up on that logic could create something that builds upon Gundam, and that’s still happening today. While the level of perfection as a work is a separate matter, I think I can be proud that I was able to create Turn A Gundam. I’m confident I created a unique work that can’t be copied. As a creator, that’s enough for me. Moreover, I’m the source of the copyable Gundam. And the post-Fukushima situation has inadvertently allowed me to present to society the themes I wanted to show in Turn A Gundam.

――Another thing I wanted to ask about is where you think animation will head in the post-Fukushima era. I’m particularly curious about what kind of work you’ll put out next. It might be impolite to say this, but your works often have elements – like Kamille’s “easily angered child” in Zeta Gundam – that become more meaningful as time passes and similar phenomena occur in society. Looking back at Turn A Gundam now, 10 years later, it stands out for its careful design and numerous keywords that seem to anticipate the current era.

Tomino: Well, you know, the crux of entertainment should first and foremost be whether it’s a hit at the time. That’s why Miyazaki’s approach is the orthodox one, and I envy it. “It has embedded words of the times,” “In retrospect…” “You understand it as you get older” – I think these are quite problematic as ways of evaluating entertainment. So, I don’t want to accept that as a form of evaluation, and I don’t think we should. But because that’s all I can do, I have no choice but to aim for it. Turn A Gundam is a work conscious of this, but I don’t think it’s good to be evaluated for that aspect. I wanted to be appreciated at the time of release, and I consider the failure to draw audiences as something to reflect on. Still, having come this far, I have a strong desire to create something that combines both immediate and lasting appeal. Why couldn’t I become a lolicon fan? (laughs) I really think it’s a flaw of mine.

I DRAW COURAGE FROM HOKUSAI’S WAY OF LIFE

――When I see a film that’s had massive production and marketing budgets and becomes a hit as expected, and then see a mountain of sponsor companies in the end credits, I can’t help but wonder – setting aside economic success – “Is this situation truly fulfilling for the creators?”

Tomino: That’s the commercialization of artistry, and I find it deplorable. But even war is driven by commercialism and market forces these days. It’s only natural that mere anime would follow suit. And while this might be considered “normal,” I don’t think it leads to much happiness for the individual… it’s more of a “nuisance,” I’d say. It’s even worse when I think, “Is this the only way my works can be screened?” While it might be gratifying in terms of recognition, it’s bothersome. Still, having numerous sponsors is proof of being acknowledged in this day and age. We should first view it as something to be grateful for… It’s the kind of recognition I’d want within reach. It’d be lonely without it (laughs). That’s precisely the frightening aspect of commercialism, and we need to be very conscious about controlling it.

For instance, in the Edo period, Kinokuniya Bunzaemon’s extravagance, built on a fortune made just by transporting oranges, helped develop the arts. Entertainment skills improve as we pursue grand extravagance. That’s also a form of culture. Culture fundamentally requires financial backing. Craftsmen can’t develop their skills if they can’t eat. However, I believe there’s a qualitative difference between the relationship of economy, commerce, and culture up to the Edo period and that of modern times. In the past, there was selection and focus, like building the Great Buddha of Nara with national finances or Kinokuniya Bunzaemon’s refined tastes. Modern times emphasize broad, comprehensive coverage. In my field, if the state started supporting even anime, that would be problematic. I’d want to say, “Be more selective!” The same applies to economic stances. During the high economic growth period, the media treated the economic section more discreetly than now, and economic papers were for industry insiders. The economy was merely something that underpinned society, but now it’s too prominent.

Of course, I’m not denying the importance of the economy. We need the real economy to keep turning. But I think virtual economics – economic theories and values-first approaches – are too prominent. Imagine how much healthier the world would be if financial jobs disappeared. Post-Fukushima, you could say we’ve become a society where such conversations are possible. We need to be careful and learn that the way of life of someone who logically pursues one thing (an intellectual) is different from realism. I want to make anime that explores such themes. At my age, with all my accumulated experiences, I’m not sure if I can create it, but Katsushika Hokusai started painting his Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji after turning 70, and before that, he even drew erotic art. I draw courage from Hokusai’s way of life. I’ve been working hard these past few years to be able to have conversations like this. I read and think more now than I did as a student. This isn’t because of my career but because my career makes me feel responsible for acquiring the intelligence to settle accounts with that career. If a million people are watching, there are a million expectations. And if you want to create something that meets those expectations, you have no choice but to study. If I thought I’d die next year, I’d want to cut unnecessary expenses, but I don’t feel that way, which is troubling.

What’s even more troubling is that I can’t read English, and I can’t improve my swimming (laughs). Facing the reality that I can’t improve such things at this late stage has been deflating these past few years. You have no idea how painful and humiliating it is to be overtaken by young folks while swimming in the pool (laughs).

――On the contrary, I feel frustrated when I’m overtaken in the pool by incredibly fit people from your generation.

Tomino: Well, we have no choice but to keep pushing each other to improve (laughs).

Source: Great Mechanics DX 18 Autumn 2011 (pages 90-94)