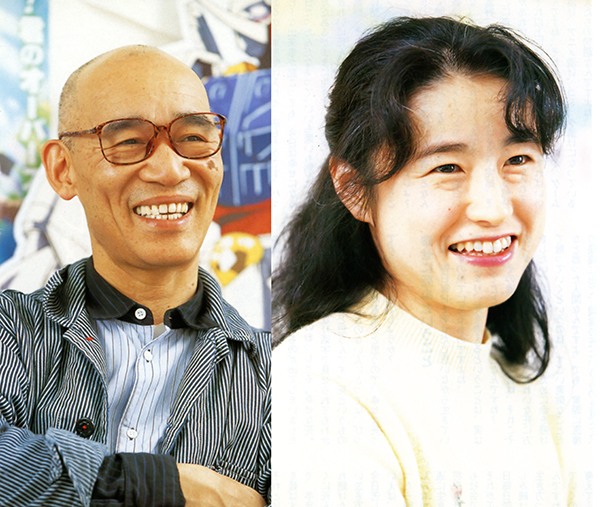

JUNKO MORITSU – Hospice Physician

Hospice Physician

Dr. Junko Moritsu

About Dr. Moritsu:

Born in Tokyo in 1963. Graduated from the School of Medicine at the University of Tsukuba. After working in hospice care, she opened the Himawari Clinic, specializing in medical consultations and counseling. Her publications include For Everyone Who Will Care for Their Mother’s Final Days (Asahi Shimbun Publishing) and The Very First Book to Read When You Are Diagnosed With Cancer (Bestsellers, Inc.).

Live happily every day. A “good death” is simply the natural culmination of a life well-lived.

Among those often referred to as the “Gundam Generation,” it seems many have only ever contemplated death as it’s depicted in anime or comics. By this I mean they understand death only as a notion inside their heads, not as a tangible reality. And if death is nothing more than an abstraction, then so too is life. The reason younger people find it increasingly difficult to grasp death’s reality is that the adults around them—parents and elders—scramble to conceal it, sidestep it, and avoid confronting it head-on. In this first conversation, I am speaking with Dr. Junko Moritsu, a physician who embraces the principle of a “good death” and lives each day in direct engagement with mortality. She has personally witnessed many end-of-life transitions. It is my hope that through this dialogue, she can offer us meaningful insights into how we might better approach our own understanding of death.

Moritsu: I’m actually part of the Gundam Generation myself. I grew up loving Gundam, pretending to play out Gundam battles with friends. It was only after I became a physician that I realized just how different death in fiction is from death in real life.

Tomino: In your book, For Everyone Who Will Care for Their Mother’s Final Days, you write that when someone is caring for a parent over the long term, there are moments when a dark corner of the mind whispers, “If they died right now, at least I could be free of this burden…” You emphasize that you must be the one who befriends that very shadowy part of yourself. Now, for me, the notion that people have a dark side is perfectly natural. The fact that you felt compelled to write it down suggests that many people don’t dare acknowledge their own capacity for “evil.” It seems there are many who honestly believe their lives can be purely “pleasant,” “cute,” “nice,” and nothing else. And they sincerely chase after such a life, when that’s not possible at all. What struck me most when reading your book was this question: Why are people so unwilling to acknowledge death? As someone working in the field, you’ve often said that you do not have the luxury of time to pontificate in song and verse, that even if death is inevitable, there can be something like a “good death.” That notion startled me—I want it to startle anyone reading this conversation too. There is such a thing as a good death, and indeed people must die. That idea is eye-opening.

Moritsu: It’s clear people don’t truly understand that death comes for everyone. Even at death’s doorstep, they still refuse to grasp it. You cannot progress any conversation until you first establish that fact.

Tomino: Is this what you typically see with your patients?

Moritsu: Interestingly, young people seem more aware of death, but only the fictional kind learned from games and anime. In that context, death can appear simple, even trivial. And because they believe it’s no big deal, many end up taking their own lives far too easily.

Tomino: As someone who creates anime, I find that interpretation so at odds with my intentions.

Moritsu: Many young people say they want a swift, beautiful end. I once spoke with a seventeen-year-old girl who took this idea very seriously. A beloved character in her favorite comic died, and she said, “I want to die too.” To her, the world she lives in seems nowhere near as beautiful as in that story; she believes no one here possesses such pure hearts. She imagines that by dying, she might reach some alternate world and finally meet these characters. She wants to die before she becomes a “tainted adult.” I can understand that feeling. When Lalah died in Gundam, I remember thinking how beautiful it would be to die the way she did. We’re all, in some sense, this troublesome generation.

Tomino: It’s actually comforting to know that a professional who deals with these realities daily understands that sentiment. A doctor who has never engaged with Gundam might fail to empathize with patients like that.

Moritsu: Precisely. If I don’t start from “I understand how you feel,” there’s no hope of my message getting through. Then I lead them in another direction by saying, “You know, in real life death doesn’t look the way it does in comics.” If I simply dismissed it as “That’s just fiction,” they wouldn’t listen. They’d shut down immediately.

THOSE WHO ACCEPT LIFE AS IT IS, LEAVE THIS WORLD IN REMARKABLE PEACE

Tomino: On the one hand, we have these young patients. On the other, much of your practice involves elderly individuals, correct?

Moritsu: Older patients have their own set of issues. Some romanticize the war they experienced, lamenting that they didn’t die heroically in a kamikaze attack when they had the chance. The war generation often splits into two groups: those who realize life is fragile and must be cherished, and those who have grown terrified of dying. Yet overall, the older generation is more grounded in the reality of death than the younger ones.

Tomino: The desire for longevity at any cost might seem like a genuine human wish, but I think it’s more of an indulgence. Wanting to die gracefully, cleanly, can be seen as an attempt to suppress one’s own selfish impulses. I believe we must cultivate a certain “death etiquette,” a personal readiness. In your experience, do you see people of my generation or older ever facing death with real dignity?

Moritsu: Some do depart with a certain graceful composure. But the vast majority still go out crying, “I don’t want to die.”

Tomino: Honestly, I’d probably do the same—shouting that I don’t want to die. But that’s exactly why I wish I could face death more elegantly. Is there no way to die without fear? Would that not be the very definition of a “good death?”

Moritsu: It comes down to not clinging to anything. Don’t fixate on the idea of dying beautifully, don’t cling to “I don’t want to die.” If an earthquake strikes, you just think, “Oh, an earthquake has come.” You accept it as just the timing of misfortune. Similarly, when something wonderful happens, you think, “Today was just meant to be a happy day.” People who live each day embracing what comes their way, without forcing themselves or repressing themselves, tend to pass quietly and beautifully.

Tomino: That strikes me as the ultimate approach to living. I understand the logic: if you can accept that fiction and real life are not the same, you might find that peace.

Moritsu: Exactly. Enjoy fiction as just that—fiction.

Tomino: In a story, a character’s death is neatly encapsulated. If something there nourishes your soul or enriches you emotionally, you can take it in, be touched by it, and then move on. The problem arises when people, hooked on games, anime, or comics, cannot make that distinction.

REAL-WORLD DEATH IS NOTHING LIKE THE DEATH WE SEE IN FICTION

Tomino: What do you believe constitutes a “good death?”

Moritsu: It’s the natural outcome of living each day with a sense of fulfillment and happiness. If you spend your life cherishing each moment, then death at the end of it can be good.

Tomino: So thinking about death is really a way of thinking about life.

Moritsu: Precisely. I grew up influenced by Gundam, wholeheartedly admiring the idea of risking one’s life for something greater, and thinking a noble, self-sacrificing death was beautiful. But when I started practicing medicine and saw death in its true form, it was utterly different. Some people endure six months of agony, thrashing in pain as we try to prolong their lives, only to die in suffering anyway. Confronted with that reality, I began to question the ideals we were taught about how to live well. There’s this tacit promise that if you suffer today, tomorrow might be easier. But the truth is, tomorrow hurts too. Six months later, you might still be in pain. In fact, that can be true even if you’re not terminally ill—it can describe everyday life.

We’ve been conditioned to believe we must endure hardship now so we’ll be happy in the future. School, work, society: all tell us to bear with it today for tomorrow’s sake. But if every day is just more hardship, doesn’t that mean we might never find relief until we die? That made me suspect that our cultural approach to life might be flawed. When I looked at people who did seem to die happily, I noticed that they simply accepted whatever came their way, never forcing themselves or pretending to be someone they weren’t.

Tomino: Your perspective carries such weight because it’s rooted in actual experience, rather than mere abstraction.

EVEN THOSE WHO ARE DEMENTED OR BEDRIDDEN CARRY A PURPOSE

Tomino: Let’s discuss something very concrete: elderly dementia patients. I’ll be frank, when it’s your own parent clinging to life in a state that’s difficult to watch, it can feel unbearably sad. I believe people should die in proper order, so why do we go to such lengths to nurse them and prolong their lives? Am I wrong to feel this way?

Moritsu: If it’s your own family member, of course you’ll feel like that. But from a caregiver’s perspective, these individuals can be a delight. When it’s not your own parent, you’re less burdened by sadness or expectations. Dementia patients express themselves honestly: if they dislike something, they say so; if they’re happy, they show it. They don’t wear masks. That honesty is refreshing to be around. If they scold me, I can just apologize. If I do something nice for them, they might flash a momentary smile—like an angel’s, really—and that one smile can bring tremendous joy.

Tomino: Still, these elderly individuals may physically harm caregivers, cause trouble, and contribute nothing to society. Objectively, are they not simply a burden?

Moritsu: I disagree. Learning to care for these patients makes us more adaptable healthcare providers. Moreover, consider their impact on young people who feel aimless and wish they could just die. When those young people provide care, they realize, “This life depends on my helping hand.” That alone can give them a genuine sense of purpose, showing them that their own life also has meaning. These patients keep others alive in spirit. They aren’t useless at all.

Tomino: Perhaps society just doesn’t know enough about what goes on in these care facilities. If people wonder, “Why work so tirelessly for these elderly patients?” then I hope young people would step inside and see for themselves.

Moritsu: Exactly. We’ve often said, “Why not have prison inmates care for them?” Because it teaches empathy. The same goes for patients in a persistent vegetative state. Before I worked in hospice care, I couldn’t understand why we kept such patients alive. I focused on the family’s suffering. But with experience, once I could view the family and the patient with equal consideration, I realized these patients aren’t “just being kept alive.” If you invest time and care, you start sensing their moods—brighter days, sadder days. They are alive, in earnest, and their presence influences us.

Tomino: But with advanced medical technology, aren’t we sometimes prolonging life unnecessarily?

Moritsu: Perhaps that’s the lesson they offer us. They show us that when we push life unnaturally, it strains everyone around them. They are, in a way, sacrificing themselves to teach us this truth.

Tomino: So does a patient ever signal that it’s okay to stop life-prolonging measures?

Moritsu: It’s not that they say “It’s fine to stop.” Rather, when they reach the point where continuing is meaningless, they will often die on their own. It’s as if they know: “I’ve served my purpose here, now let me go.”

Tomino: They simply pass away.

Moritsu: Yes. When a caregiver is on the brink of collapse, that’s when the mother might slip away. They seem to time their departure as if to say, “You’ve done enough.”

Tomino: Fascinating. Human beings do not live in vain, it seems.

Moritsu: Certainly not. People who insist, “I never want to end up on a ventilator,” generally never do. They pass before it comes to that. Even if we try every intervention, their heart will simply stop.

Tomino: This is exactly the sort of life-and-death reality I wanted to hear about.

THE DISTORTIONS OF CONCEALING LIFE AND DEATH ARE REFLECTED IN TODAY’S SOCIETY

Tomino: Postwar Japan changed so drastically. We hardly ever see raw ingredients anymore. Pre-packaged, ready-to-heat meals are the norm. We’ve lost the feeling that we’re sustaining ourselves by taking other lives, fish, livestock. We don’t want to see animals slaughtered or even imagine it. We’ve cut ourselves off from that reality. Likewise, we’ve hidden birth and death behind hospital curtains. Long ago, people gave birth at home and died at home. I do have vague childhood memories of seeing both, but now it’s all out of sight. Add to that our sanitized food culture, and it seems younger generations have no direct physical sense of life and death. Saying “Cherish life” to them is pointless if they’ve never felt what life and death truly mean. We cannot teach this through ideals alone, can we?

Moritsu: It’s impossible. Without that grounding, we get only superficial responses. That’s why people end up on life-support machines covered in tubes, desperately clinging to life. Children who grow up never seeing death become abnormally sensitive to it when it does appear. The first time they truly encounter death, it causes chaos. They overreact, and that forces the family, the society, to confront what they’ve avoided. On one hand, I sense an increase in children with extremely keen sensitivities, who have violent emotional responses when they encounter something outside their neatly defined boundaries. That turbulence compels families and society to finally think about these issues. Any distortion we create ends up manifesting somewhere else, forcing a reckoning.

Tomino: You’re remarkably philosophical about it. I still feel the urge to find a solution.

Moritsu: I also want to do something about it. But if children react this way, it may be precisely because our society needs that reaction. Perhaps we should watch calmly, step back, and provide only the necessary support. Basically, I approach it with a cool eye and a readiness to do what must be done, no more, no less.

Tomino: So it’s not really a problem with the younger generation. It’s my generation, and those older, who constructed the systems that hide home births, shroud death, and sanitize our food and funerals. We deprived them of firsthand encounters with life and death. Now these children grow up in a sterile environment, and though they seem overly sensitive, they’re actually striving to adapt in their own way. My generation had at least some foggy memories of life events, yet we failed to accumulate real experience with births and deaths. We grow old without ever becoming true elders ourselves.

Moritsu: Every generation has its challenges. Eventually, the consequences circle back. If we create a medical system focused solely on prolonging life, we will be subjected to that system when our time comes. Only then do we realize our mistake. It’s inevitable.

Tomino: That realization is brutal. I want to fade out gracefully, but instead I’m stuck confronting our collective folly now, at this late stage.

Moritsu: Yet those who do realize the problem are already carving out new options. The existence of hospices, for instance, came from people questioning the old system. Some began thinking, “Shouldn’t we strive for a good death?” Those who consider life and death seriously do find their way to these places.

Tomino: Japan is experiencing unprecedented longevity, and yet many still crave more years without fully understanding what it means to grow old. They ignore how difficult living can be and permit themselves the vanity of never-ending life. I think that’s extreme. We should be more willing to accept the natural order—birth and death—and internalize it. Now that I’m older, I’m starting to think about how we cultivate an acceptance of death. How does one develop that capacity?

Moritsu: That is a difficult question. Even though I work with the elderly daily, they still surprise me. I don’t fully grasp what aging feels like, and I never will until I face it myself. Death may remain incomprehensible until we die. If I had more opportunities for the young to engage with older people—truly engage—it might alter their perceptions. But as it stands, it’s hard.

Tomino: I have no elders around me who can teach me these things. Without mentors shaped by natural forces, I have no real “feel” for aging. Thus, all I can do is think and think, going in circles. I envy your position, surrounded by older individuals, able to learn from them. From your vantage point as a physician, if you were to convey the essence of “what life is” to ordinary people, what would you say?

Moritsu: What could I say…? Perhaps when we die, we each discover our own meaning. Maybe we can only understand it then.

Tomino: So at the very least, we should live in such a way that we’re able to discern our own meaning at the end. That’s something we must at least strive to keep in mind.

Moritsu: Yes. I believe so.